“In an uncherished field…”

by cjdown

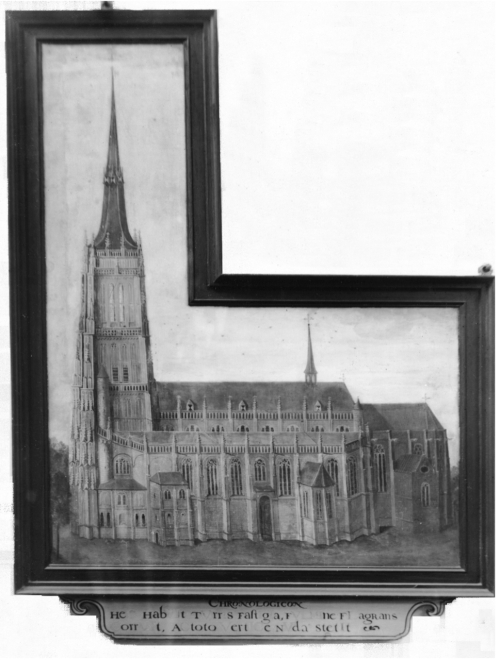

“In an uncherished field beyond a subdivision in the refinery town of Texas City, Texas, I got interested in four radio towers that collectively formed what is called a ‘directional signal’. I chose a vantage point at the corner of the field on the shoulder of an embanked road; it overlooked the confluence of two rainwater ditches running at right angles to each other along two borders of the field. To look down into the ditches and up at the immense spindly height of the towers, with their barely discernible guy wires, comprised a vertical span of a little more than 90 degrees. The canvas then, once the preliminary drawing was worked out ended up being nearly square, 46 by 48 inches. My notion of the right relationship between interior forms and spaces of a painting and its containing periphery is perfectly expressed by an early (circa 1562) Dutch image of a church painted on an L-shaped panel; the nave occupies the thick base of the L and the tower its slim shaft. I refer to this as the ‘L-shaped church paradigm’.

Around this time I read that Ruskin had told his followers, ‘When I say go out and paint Nature, I do not mean a ditch.’ I thought, Thank you, John, because these ditches not only form a remarkable rectilinear grid of narrow incisions in the terrain that shoot dramatically off into space, but in this dead-flat, hurricane-prone, barely above sea level coastal country they are a crucial part of the functional system of levees, raised roads, and ‘Archimedes screw’-type pumping stations that, as with the reclaimed polders of Holland, is essential in making this land usable and inhabitable at all. Children play in these ditches, fishermen get bait out of them, and weeds flourish there unmolested. Alongside the embanked roadway in this painting run power and phone lines which (as we know) sag as they stretch from pole to pole; but if you stand close to them, as I did while working, and follow them with your eyes as they pass from left to right of you, they soar up in the air and arch over your head; their appearance contradicts what we know. Uncompromising empiricism may lead to paradoxes.

These extended spaces, then, that I was working with, and the way forms bulk in them, plus the effect of specific vantage point and bodily stance on one’s perception of them, began to present endlessly fascinating problems of depiction …

The question arises as to whether, if space appears to be curved, it is concave or convex. It may be both. The horizon wraps around you as a room contains you: it is concave. But suppose you are sitting in a room opposite the midpoint of a long wall; as your gaze follows the wall from either corner to the midpoint, the wall appears to swell toward you: it is convex. Frankly, though, these diagrams of space never interested me very much. The ‘truth’ of any one of them is contestable (and endlessly contested): they are, precisely diagrammatic, as well as systematic, theoretical, designed for general application. But I don’t find that I see systematically. I – we – have erratic, not to say subjective, reactions to size and scale; we do all kinds of things when looking: we shift our attention, turn and tilt, quickly or slowly, get interested in some things and uninterested in others. The process of looking – especially the process of looking while making a drawing or a painting – is far too alive and spasmodic to be rationalized.

To any diagram I prefer – and trust – the experience-based statement of Cézanne: ‘for progress toward realization there is only nature, and the eye is educated by contact with her. It becomes concentric by force of looking and working.’ Does Cézanne mean concentric to the viewer? Are we inside the sphere that Fouquet’s miniature implies and that Leonardo conceived in his notes? Certainly this is a manifesto in favor of committed empiricism. Eschewing theory and system, protocol and precedent, Cézanne wants to know only what he learns from the practice – his practice – of painting.”

(Rackstraw Downes, “Turning the Head in Empirical Space”, in Rackstraw Downes, Sanford Schwartz, et al. pp.129 – 143)

Video of Rackstraw Downes talking about his work.

Thanks for posting this Chris. It is a great start to my first year foundations teaching day.

Glad you liked it Ila!