In his recent article, Is De-skilling Killing Your Arts Education?, F. Scott Hess rails passionately against an alleged prejudice toward “skilled” representational painting in contemporary art education. I have heard some students and fellow artists voice similar worries, implying that because drawing from life and traditional technique are no longer the focus of most art school curricula, that artistic skill is banished, replaced instead by faddish academic trends. There is an added edge to these complaints when tuition costs are soaring and students seek practical skill sets in return for their investment. It is frustrating and discouraging for students when they perceive that their work is unappreciated, even when it is highly accomplished on a technical level. However, the tone of Hess’ narrative suggests that the crux of the issue is not a simple intolerance of skill, but is instead the result of contentious disputes over how art is understood to function in contemporary society.

It is important to be specific about what is meant by skill in this context. Hess equates skill with drawing the human figure, and more generally, the knowledge and procedures embedded in classical representational painting, such as anatomy, perspective, and mastery of technique. It is this approach in particular that is seen to be the victim of censure:

I wish I could say this academic prejudice against skill was a thing of the past. Unfortunately, it is stronger now than it has ever been. Conceptualism replaced abstraction as the dogma of the day, and has been in turn replaced by Postmodern hybridity, identity politics, or pure theory on the majority of college campuses. As in all educational endeavors, young minds are molded to fit the norm their professors set forth. De-skilling is the term I’ve commonly heard used to describe this odd institutional practice in the arts.

The idea that you might train a surgeon to be clumsy, or an engineer to build poorly, or a lawyer to ignore law, would be patently absurd. In the arts, however, you will find an occasional musician who purposely plays badly, or a writer who ignores grammar, but only in the visual arts is training in the traditional skills of the profession systematically and often institutionally denigrated.

It is reasonable to wonder about the priorities of educational institutions that would allow such seemingly large gaps in the training of artists. However, I think there are two distinct issues at stake in Hess’ account. The first is the question of what constitutes skill and whether or not it is transmitted in art education. The second is the status of the academy in relation to its capacity to institute and regulate its dogmas and norms.

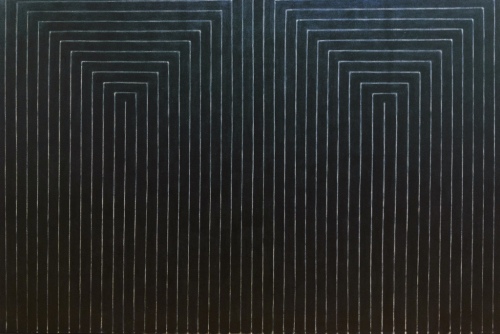

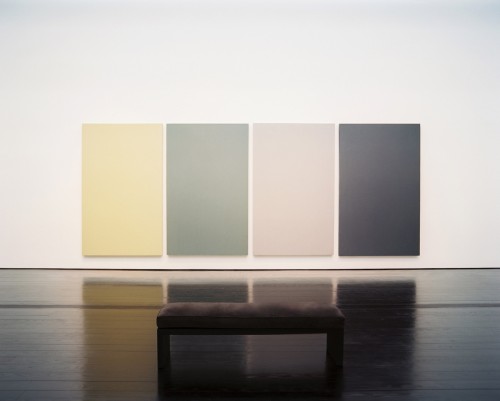

According to the terms that Hess sets out, there is definitely a systematic thrust by artists from the late 19th, and into the early 21st centuries to de-skill art production, and this is reflected and reinforced in the educational institutions that train artists in the modern period. This process begins with the rejection of academic standards of decorum, finish, and hierarchies of subject matter by artists like Courbet and Manet, and moves through the succession of “isms” into the 20th century. Although many of the early modern artists that are revered today had some kind of academic training, their refusal to perpetuate the standards of the academy did not come out of boredom or perversity, but from the recognition that these conventions were somehow inadequate to represent the rapidly changing world they lived in. In this case, according to John Roberts, the question becomes:

how do I paint convincing images that express the truth of what it is like to live under these new conditions? As a result, painterly technique becomes a highly contentious matter in the bid for non-academic status and value; technique, it is asserted, is not a neutral skill, something transmittable down the ages, but, rather, historically contingent, and therefore inseparable from the demands of artistic subjectivity and the artist’s mode of vision. Questioning inherited technique then became a means of questioning the link between academic technique and form in official or salon-painting. (80)

Edouard Manet, Luncheon in the Studio, 1868

Hess’ comparison between training clumsy surgeons and the “denigration”, in visual arts, of “training in the traditional skills of the profession” is misplaced because it assumes that achievement in each field can be measured against a similarly stable set of criteria. A surgeon without the requisite hand-eye coordination would not make it very far in their education, but it is also true that a surgeon that insisted on the value of the “traditional” techniques of bloodletting would have a hard time convincing the medical community of its value. Technology, technique, and research have rendered bloodletting obsolete as an effective means to obtain the goals of surgery. Within the visual arts, however, it is still possible to use the most ancient technical approaches (such as painting) and remain relevant, if they are deployed in such a way that they produce meanings that continue to have resonance within the culture.

Roberts refers to this modern questioning of inherited technique as “deflationary strategies”, and he connects these impulses with artistic methods such as collage, assemblage and the ready-made, which initially introduce “non-art” materials onto the surface of paintings, and then become independent approaches in themselves (82). Once modern artists established these strategies in opposition to the standards of academic painting, artistic technique could no longer be held as stable and therefore “artistic form is not able to be assessed from any normative standpoint”(81). Roberts continues:

As Duchamp’s notion of the ‘rendezvous’ suggests, the superimposition and reorganisation of extant forms and materials opens up the category of art to non-artistic technical skills from other cultural, cognitive, practical and theoretical domains: film, photography, architecture, literature, philosophy and science. Indeed, if art is a site of many different disciplines, materials, and theoretical frameworks, art can be made quite literally from anything. (83)

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59

One of the results of this shift is that manual skill at representation no longer occupies a prominent place among the criteria for judging artworks. This in itself does not prevent the teaching or acquisition of these skills, but their priority in educational practice is diminished in favour of different skills, many of which might be described as involving conceptualizing or arrangement, rather than hand-eye coordination.

This short detour into the history of artistic de-skilling illustrates that the supposed prejudice against skill is not arbitrary, but is part of a critical response by artists to the conditions of modernity itself. It is something of a red herring to construct this as a tyrannical edict from the corrupt ivory tower. Further, complaints against abstraction, conceptualism, hybridity, identity politics, and so-called “pure theory” seem to ignore the fact that western society as a whole has moved toward diversity of voices and plurality of practices, and art-making is not exempt from these tendencies, nor should it be.

Fluency in the language of materials and their modes of application are the bare minimum for any kind of achievement in drawing and painting, but they are not sufficient in the absence of other cognitive aspects of art-making, and I submit that this is not any different today than it was in the 15th century when the “traditional skills of the profession” were codified.

De-skilling in art ought to be seen in the historical context from which it derives. Skill, as such, is not absent from modern artistic training, but the focus of this training is no longer directed toward the manual dexterity and disciplined technique prevalent in the pre-modern era. For better and worse, these are the conditions that contemporary art inherits from the last 150 years of practice.

But Hess’ complaint, I think, is actually less about whether students develop skills in art school, than the sometimes toxic discursive and critical environment that they have to navigate while sorting through which skills to take up and which to set aside. I will address this question in a future post.

Cited

Hess, F. Scott. “Is De-Skilling Killing Your Arts Education?”, Huffington Post: Aug 30, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/f-scott-hess/is-deskilling-killing-you_b_5631214.html

Roberts, John. “Art After Deskilling”, Historical Materialism 18 (2010): 77-96. http://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/robertsjohn_artafterdeskilling2010.pdf